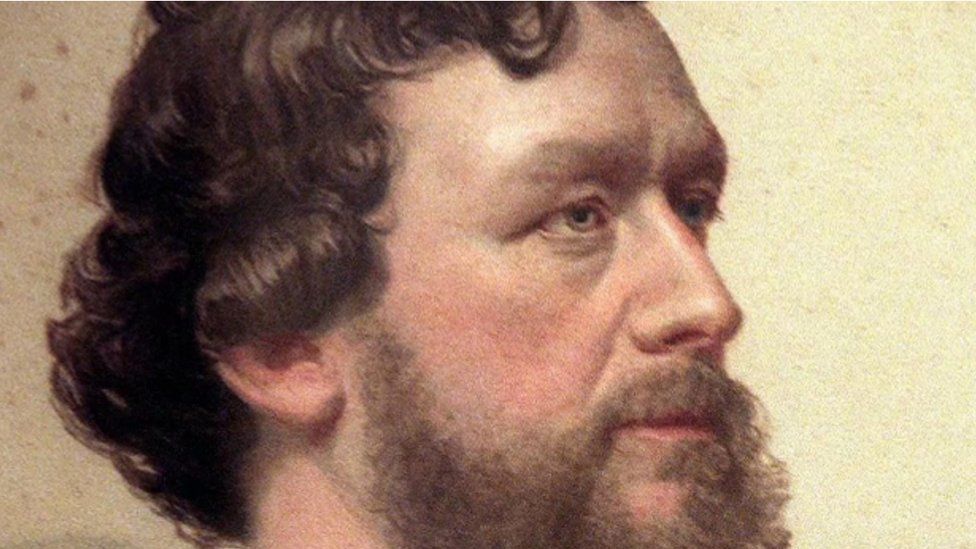

Greek Thomson: Scotland's other great visionary architect

- Published

Alexander 'Greek' Thomson did more to transform Glasgow into a city fit to be described as the "Second City of the Empire" than any other architect.

The booming powerhouse city, which quadrupled in size between 1800 and 1850, needed a new vision as it expanded out from the old slums and Thomson was the man who supplied it.

However, the city on which he made his mark during the Victorian era later allowed his legacy to fall into neglect.

When Glasgow council was planning to demolish one of Thomson's landmark churches in 1966, influential American architectural historian Henry-Russell Hitchcock made a plea for them to stop.

He said: "Glasgow in the last 150 years has had two of the greatest architects in the world."

He named Charles Rennie Mackintosh as one and Alexander Thomson as the other.

Scottish actor David Hayman, who presents the BBC documentary Greek Thomson: Glasgow's Master Builder, says: "The name Charles Rennie Mackintosh is known around the world but I believe that Alexander Thomson was perhaps an even greater visionary."

Who was Alexander Thomson?

Thomson, who was born 200 years ago next week in the Stirlingshire village of Balfron, acquired the nickname 'Greek' despite rarely leaving Glasgow and never setting foot abroad.

He was brought up as a strict Presbyterian and held to his faith throughout his life.

Thomson presented himself as a hard-working businessman rather than an artist.

Maybe these factors could explain why the reputation of the man, who was happily married with seven surviving children, has not caught the public imagination in the same way as the glamorously brilliant Mackintosh and his waxed moustache.

Thomson was more productive than Mackintosh, many of whose projects were never realised, and he was acutely aware of the problems of urban living in one of the most densely-populated cities in Europe.

Thomson was one of 20 children and by the age of eight he had moved to Glasgow with his widowed mother.

He was orphaned six years later.

Four of Thomson's own children died of cholera.

Why is he Greek?

Thomson only became 'Greek' in the mid-1850s, in his late-30s, when he decided to adopt the Classical Greek style as his only mode of working.

Before that he had designed many gothic, baronial, and Italianate villas down the Firth of Clyde in places such as Cove and Kilcreggan.

He adopted the Greek at a time when it had gone out of fashion, especially in England where Gothic Revival was all the rage.

The building that marks the moment when Thomson became Greek is the Caledonia Road Church in the Gorbals, just south of the River Clyde near the city centre.

The dramatic structure still dominates the city skyline but it has been a derelict ruin for half a century.

Sally White, from the Alexander Thomson Society, says: "It was described by Henry-Russell Hitchcock as one of the finest, if not the finest, Classical Romantic churches in Europe.

"Many architects have used Classical architecture and its principles and produced beautiful buildings, but Thomson didn't recreate them, he understood the language, he understood the complex geometries, he understood the mystical qualities of it and he then interpreted that in a very individual, unique way.

"I think that's the difference."

Thomson's landmark churches

The Caledonia Road Church, where Thomson himself worshipped, fell into disuse as the Gorbals, which had become an area notorious for poor housing and health, was cleared in the mid-20th Century.

In 1965 the empty church was torched by vandals and the council, which had responsibility for it, wanted to knock it down.

Architectural historian Gavin Stamp says it might not be standing now if Hitchcock had not published a letter in the Glasgow Herald, claiming that "it is without question the most remarkable and most distinguished ecclesiastical edifice of the high Victorian decades".

Another of Thomson's Presbyterian kirks, perhaps the most dramatic of all, Queen's Park church, was destroyed by an incendiary bomb dropped by the Germans in 1943.

One notable survivor is St Vincent Street Church in the heart of Glasgow city centre.

Built in 1859, it is a jaw-dropping monolith.

Evan Macdonald, an elder of the Free Church, says: "Thomson was a man of faith and his faith influenced his architecture. He took some references from the Temple of Solomon but more than that there is Egyptian, Assyrian and Classical influences."

Indeed, many architects think the Greek nickname to be something of a misnomer.

Thomson took Classical Greek principles based on a strong post-and-lintel system and adapted it using his own vision.

He was inspired by the Old Testament paintings of John Martin and his visions of a heavenly architecture.

But Thomson brought in other influences and he was equally Egyptian Thomson, Assyrian Thomson and Modern Thomson.

Saved for the nation

Other Thomson buildings to disappear are his tenement on Queens Park Terrace, which was bulldozed as recently as 1981, and Cowcaddens Cross which went a decade earlier.

Thomson's finest villa, Holmwood House in Cathcart, a Victorian suburb about four miles from the city centre, was saved by a small band of enthusiasts 25 years ago and is now cared for by the National Trust for Scotland.

It was completed in 1858 and designed for the wealthy paper maker James Couper, as both a family home and somewhere for him to entertain business clients.

Architectural historian Gavin Stamp, who launched the campaign to save Holmwood, says: "It was occupied by an order of nuns who were selling up and a developer had an option on it and the plan was to cover the grounds with blocks of flats.

"Its future was uncertain so we thought it ought to be rescued and put in the hands of an organisation that could look after it."

Mr Stamp adds: "It's wonderful to come here now and see the restoration that is slowly going ahead.

"It was the first picturesque Grecian villa, by that I mean it is asymmetrical, a building to be seen from different angles.

"Before this, Grecian villas tended to be entirely symmetrical.

"Thomson's asymmetrical villas down the Clyde at Cove and Kilcreggan tend to be Italianate, Gothic or Baronial, but having found his language, the Greek, he used it in a new way. This asymmetrical Grecian villa is the first of its kind."

Holmwood House is a breakthrough building, a brilliant fusion of different styles.

Thomson broke down the old rigid restraints of Greek Revival architecture and introduced a romantic freedom and honesty.

Tenements and terraces

It was not just rich men's houses that Thomson built.

He also designed tenements such as Walmer Crescent, which is now next to Cessnock underground station, south of the river, and Great Western Terrace in the west end.

In 1861, Thomson moved his family to Moray Place, a beautiful terrace in the Southside suburb of Strathbungo, that he designed himself.

Presenter David Hayman visits the home Alexander Thomson designed for himself

Commercial premises

Thomson's Grecian chambers on Sauchiehall Street are today home to the Centre for Contemporary Arts.

It was originally designed for shops and found an ingenious solution to changing the streetscape from the villas that were already there.

Architect Karen Pickering says: "He built the Grecian Chambers then he excavated underneath the existing villa. So the villa is actually sitting on stilts. surrounded by other buildings."

Another Thomson masterpiece, built in 1873, is the Egyptian Halls, which contained everything from shops, to lecture rooms to exhibition spaces.

Today the exotic building on Union Street is surrounded by scaffolding with only a painted plastic shroud hinting at what lies beneath.

John Addison, a conservationist and engineer who has been involved in the attempt to bring the Egyptian Halls back to life, says: "It would be tragedy to lose the thing because this glorious piece of Thomson architecture reflects a great architect in a great city."

Greek Thomson's legacy and reputation

In the winter of 1874/1875 the asthma that had plagued Thomson all his life grew steadily worse. He died on 22 March 1875, at the age of 57.

Architect Fiona Sinclair says she thinks Thomson's reputation suffered at the time and since because he came from the provinces.

She says: "In addition to which he railed against the Gothic style which was the most popular style of the period, particularly in England, and I think that made him deeply unfashionable."

The new Glasgow University building, which was being built in Thomson's final years high on Gilmorehill in the west end, represented the triumph of the Gothic over the Greek.

It was built by fashionable London architect George Gilbert Scott.

Thomson hated it and said its mock medievalism made it a laughing stock.

However, Gothic dominated the subsequent decades and it was not until a new generation such as Frank Lloyd Wright in America, Mies Van Der Rohe in Germany and Le Corbusier in France began to think about new ways of designing and building that Thomson's elemental philosophy began to be reconsidered.

Architectural historian Gavin Stamp says: "There is an argument that Thomson anticipated certain aspects of modern architecture. He created his own extraordinary style of architecture rooted in the past but yet something new.

"He's a towering figure. A great mind as well as being a brilliant architect. I'd put him top."

A few years after his death, his friends decided on a tribute to him.

They honoured a man who had never been abroad with a travelling studentship to promote the study of Classical Architecture.

One of the early winners of the award was a young man from the east end of Glasgow called Charles Rennie Mackintosh.

- Published18 March 2015