Xi is not the boss in US-China struggle. Neither’s Trump. Here’s who is

- As the Chinese and American presidents meet at the G20 summit in Japan both are ultimately trying to appeal to one group of people

- The Chinese middle class is the greatest economic asset on the planet

Who are the people in charge of the new China which is flexing its muscles almost daily across the rest of the world? Who has most power in this story of China’s renaissance, as it becomes so important even the mighty US now has to pick fights with it in order to restrain it?

But look a little harder, and there are other figures lurking in the background, and making up a much vaster and more deeply powerful cohort. These are not even in the party. They are not an easy group to adequately describe and conceptualise. This is for the very simple reason that their existence and their emergence is so recent that no one, inside or outside China, has had much time to work out their meaning and what kind of common identity they might have.

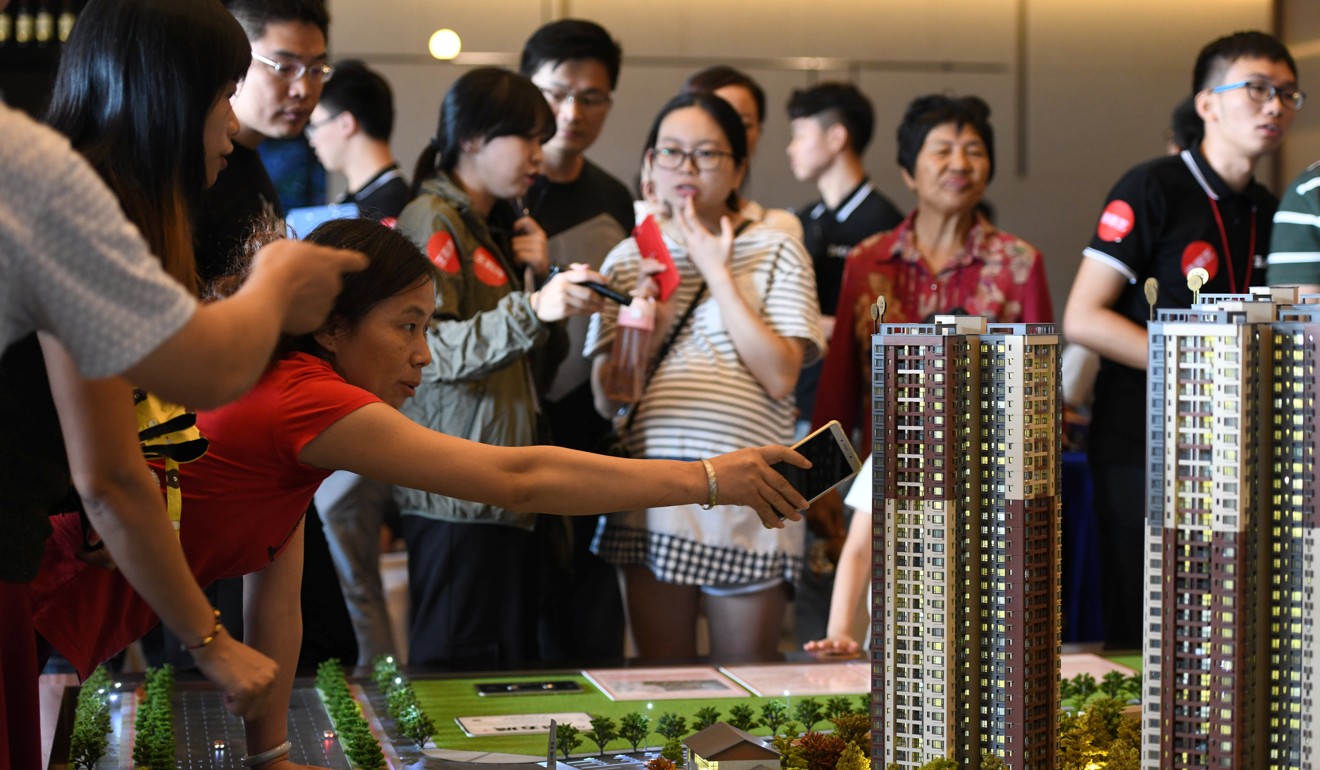

These days, though, it is the car owning, commuting, mortgage paying, Western-branded-clothes-wearing bourgeoisie of China that matter most. The irony is rich. The world’s largest state where a single party has a monopoly on power – and a communist one at that – is also the one where a middle class like this seems to be increasingly central to government, and international, intentions.

There is one simple reason for this. This middle class lies at the heart of all the key hopes of Xi’s government to change the structure of the Chinese economy to a higher-quality one, and to make China a global innovation leader. Its members are also, as yet, surprisingly low consumers. Napoleon, according to legend, says when China stands it will shake the world.

China thinks it can weather trade storm. It can, but not for long

In fact, we can update this. When this middle class spends like its equivalents elsewhere, it will not only shake the world, but probably tilt it from its axis.

Xi speaks to this group, with their aspirations and their complexity, in the language of nationalism. While there are plenty of party members in its ranks, the vast majority are non political – but that does not mean they are apathetic. They want to see their country accorded a high status. They celebrate with their formal political leaders China’s renaissance, and they are glad to see their country paid global respect.

The Chinese middle class is the true heart of the modern Chinese story, and the key voice dictating how this will unfold. Xi, in many ways, is their servant. Were he ever to lose their support, he and the party he leads would quickly be gone.

This is unlikely today, when growth is around 6 per cent. Lower than this, and the country that has never known recession in 40 years stands a good chance of becoming a very different place, one far less hospitable to Xi’s style of autocratic rule.

Trump’s biggest mistake: not realising China will never genuflect again

One final thing to remember is that this group is the greatest economic asset on the planet. Its ranks are likely to double in the next decade or so. These people are the ones that the US, Europe and others want access to – to sell goods, services, and to see if they are more politically open minded than their current rulers. One thing we can say with certainty – perhaps the only thing – is that this group is not an uncomplicated one.

No one, neither in Beijing, nor Washington, nor Brussels, should be complacent about their capability and their potential impact on the world.

They are the masters of the story we are seeing. The current leaders in Beijing are simply the shadows standing before them. ■

Kerry Brown is professor of Chinese Studies and director of the Lau China Institute at King’s College, London, and an associate on Chatham House’s Asia-Pacific Programme