The Internal Memo That Allowed IBM's Female Employees to Get Married

When Eleanor Kolchin worked at IBM in the late 1940s she had to keep her marriage a secret.

In 1946, Eleanor Kolchin's father came home with the news that IBM was hiring mathematicians Kolchin was a math major and had already sent out application for a math Master's degree, in the hopes that she might someday become a teacher. She decided to send IBM a letter as well, and pretty soon she had her first full-time job.

Kolchin, who is now 86, recently recalled those early days of the computing industry in a fascinating interview with the Huffington Post's Bianca Bosker. Women, in those days, were seen as temporary hires, holding a spot for a man, which she would relinquish if she got married. Kolchin herself got married, but did so "on the sly." As she explains in the interview:

What was it like to be a woman working in a computing lab?

At that time, IBM fired you if you got married. The reason was, it was the end of the war and they wanted to hire people who had fought in the war, who were then coming back from World War II and wanted jobs. I think you could understand that, and people did understand that at the time.

So were you able to keep your job when you got married?

I did get married on the sly. And then in 1951 they changed the law, and I got married.

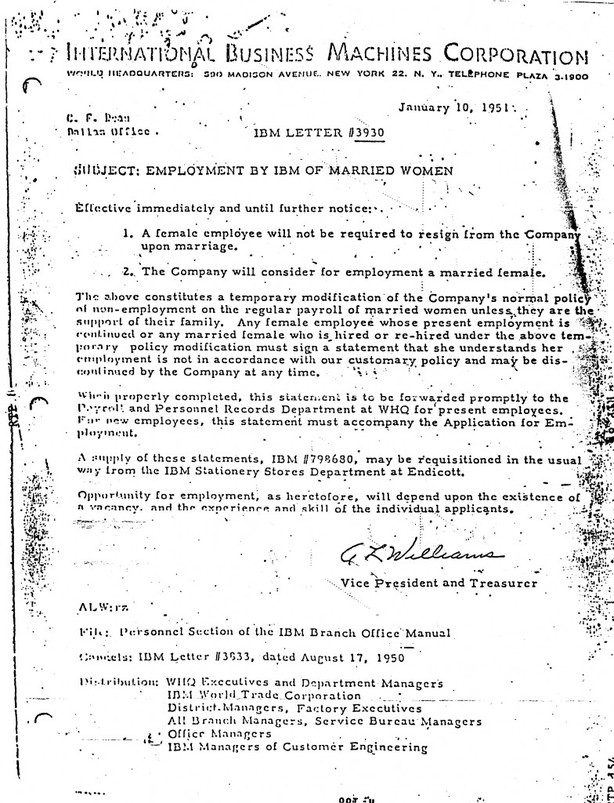

The "law" Kolchin refers to is not so much a law but a company policy -- one that IBM rescinded in 1951 with IBM LETTER #3930, which Sociological Images got a hold of in 2010. "Effective immediately and until further notice," the memo read, "1. A female employee will not be required to resign from the company upon marriage." And, it continued, "2. The Company will consider for employment a married female."

According to the interview, which is really worth reading in full, Kolchin still programs, maintaining the website and weekly email of the Boca West Special Interest Club. She loves her iPod, whose storage capacity amazes her.

"When they were computing the orbits of outer planets on the SSEC [IBM's Selective Sequence Electronic Calculator, which operated between 1948 and 1952] the machine took up an entire room, including the ceiling, under the floor and all the walls," she tells Bosker. "My husband has 13 symphonies on his iPod Mini and they only take up a third of the space. That boggles my mind. You don't even know what a miracle you're living in."

And that's true. We really don't.