What Mueller's Indictment Reveals

The special counsel detailed how a Russian effort to widen divisions in American society launched in 2014 morphed into active support for the candidacy of Donald Trump.

A 37-page indictment filed by Special Counsel Robert Mueller on Friday lays out the most detailed picture of how the Russian government sought to interfere in the 2016 election, meddling with voters to sow division in American society, and encouraging the election of Donald Trump in what the defendants referred to as “information warfare against the United States of America.”

“The conspiracy had as its object impairing, obstructing, and defeating the lawful governmental functions of the United States by dishonest means in order to enable the Defendants to interfere with U.S. political and electoral processes, including the 2016 U.S. presidential election,” the indictment states. There are 16 defendants, including three organizations and 13 individuals, who are charged with conspiracy to defraud the United States by impairing enforcement of election law as well as wire fraud and bank fraud.

The document is the most complete set of allegations offered by the government yet about one subset of Russian interference, going far beyond an intelligence-community report released in early 2017. At its peak, the alleged conspiracy had a budget of more than $1.25 million per month for activities in the U.S. and elsewhere.

The indictment also stands as an implicit rebuke to President Trump, who has repeatedly refused to acknowledge the Russian role in the election, saying many actors may have been involved. He has also rejected the idea that any interference might have aided him. His rejection puts him at odds with the entire American intelligence establishment, which has concluded that Russia interfered. On Tuesday, top officials, many of them Trump appointees, reaffirmed that stance and said Russia would also seek to meddle in the 2018 election.

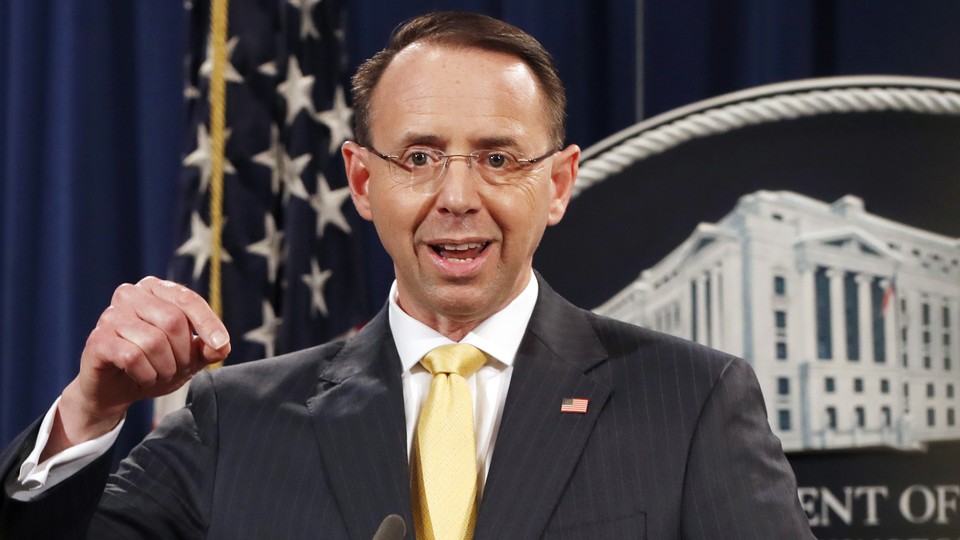

The allegations contained in this indictment, returned by a federal grand jury in Washington, D.C., do not reach the most politically contentious questions in Mueller’s view. They do not concern the hacking of emails from the Democratic National Committee, Clinton campaign officials, and the Republican National Committee. They don’t address questions of collusion between the Trump campaign and Russia; indeed, this indictment states that Russians had some contact with Trump officials, but Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein said Friday that “there is no allegation in this indictment that any American was a knowing participant” in law-breaking. He added, “There is no allegation in the indictment that the charge conduct altered the outcome of the 2016 election.” Neither does this indictment touch on whether Trump obstructed justice.

Nonetheless, the indictment makes it difficult for Trump to continue to claim that Russia did not interfere in the election. It states:

Defendant ORGANIZATION had a strategic goal to sow discord in the U.S. political system, including the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Defendants posted derogatory information about a number of candidates, and by early to mid-2016, Defendants’ operations included supporting the presidential campaign of then-candidate Donald J. Trump (“Trump Campaign”) and disparaging Hillary Clinton.

When the intelligence community has previously leveled that charge in the past, it has offered only vague evidence, basically asking for the benefit of the doubt. That allowed skeptics of the intelligence agencies, as well as Trump and his allies, to cast doubt on the claims. Friday’s indictment contains far more detail, and while its contents are allegations, not claims proven in a court, they are bolstered by extensive documentary evidence, including emails and messages. Much of the material has been reported in various news outlets, but the indictment puts it all in one place for the first time.

Here’s what the indictment lays out.

The Russian effort to meddle in the election began way back in 2014, long before anyone viewed Trump as a serious candidate for the presidency, much less a likely nominee. The goal was simply to create division and chaos by exploiting existing cleavages in American society—or as the indictment puts it, operators were instructed to create “political intensity through supporting radical groups, users dissatisfied with [the] social and economic situation and oppositional social movements.”

The work was coordinated through the Internet Research Agency, a group that came to widespread American attention in summer of 2015, when Adrian Chen wrote a long feature on it for The New York Times Magazine. The IRA is a private company, not a government agency, but as Chen laid out, it has close ties to the Kremlin. The indictment explains that the IRA in turn was controlled by Concord Management and Consulting and Concord Catering, “related Russian entities with various Russian government contracts.” Concord hired the IRA for “Project Lakhta,” a wide-ranging project that involved work in Russia and overseas.

The IRA and its officers began tracking U.S. social currents in 2014. That year, two of the defendants named in the indictment traveled to the United States for scouting purposes. The indictment describes measures that would seem cartoonish if not for what would follow. The travelers claimed they were visiting for personal reasons, but bought special equipment and discussed “evacuation scenarios” for the trip. In June, two of the defendants covered a great deal of ground, going to Nevada, California, New Mexico, Colorado, Illinois, Michigan, Louisiana, Texas, and New York. In November of 2014, a third defendant visited Atlanta.

When Chen reported on the IRA, many of the initiatives he uncovered were laughable—bizarre in concept, sloppy in execution, and without much sway in practice. Early on, Project Lakhta’s efforts seemed similarly amateurish. Posing as Americans, they sought advice:

For example, starting in or around June 2016, Defendants and their co-conspirators, posing online as U.S. persons, communicated with a real U.S. person affiliated with a Texas-based grassroots organization. During the exchange, Defendants and their co-conspirators learned from the real U.S. person that they should focus their activities on “purple states like Colorado, Virginia & Florida.”

Any casual American watcher of politics could have offered such a banal insight, but it was influential for the Russians: “After that exchange, Defendants and their co-conspirators commonly referred to targeting ‘purple states’ in directing their efforts.”

The work soon started to bear fruit. “Specialists” at IRA began creating social-media pages devoted to hot-button issues, from restrictive immigration policy to Black Lives Matter to religious affinity (“United Muslims of America,” “Army of Jesus.”) “By 2016, the size of many ORGANIZATION-controlled groups had grown to hundreds of thousands of online followers,” the indictment states. One particular notorious example was a Twitter account using the handle @TEN_GOP, which purported to be the voice of the Tennessee Republican Party. “Over time, the @TEN_GOP account attracted more than 100,000 online followers,” the indictment states.

Vladimir Putin’s government has long detested Hillary Clinton, and as Trump rose, the IRA seems to have concluded that he was a useful vector for grievances. Employees sought to boost Trump and Bernie Sanders, Clinton’s principal primary opponent, while also attacking GOP candidates who were more hawkish on Russia: “They engaged in operations primarily intended to communicate derogatory information about Hillary Clinton, to denigrate other candidates such as Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio, and to support Bernie Sanders and then-candidate Donald Trump.”

Shortly before the election, an Instagram account called “Blacktivist” posted, referring to the Green Party candidate, “Choose peace and vote for Jill Stein. Trust me, it’s not a wasted vote.” Another implored African Americas to boycott the polls: “[A] particular hype and hatred for Trump is misleading the people and forcing Blacks to vote Killary. We cannot resort to the lesser of two devils. Then we’d surely be better off without voting AT ALL.”

Even if the conspiracy did not set out to boost Trump, it jumped into the task with gusto once latching on to him. There was a distinctly pro-Trump bent in its social-media presence:

Certain ORGANIZATION-produced materials about the 2016 presidential election used election-related hashtags, including: “#Trump2016,” “#TrumpTrain,” “#MAGA,” “#IWontProtectHillary,” and “#Hillary4Prison”" Defendants and their co-conspirators also established additional online social media accounts dedicated to the 2016 U.S. presidential election, including the Twitter account “March for Trump” and Facebook accounts “Clinton FRAUDation” and “Trumpsters United.”

The indictment also cites a September 2016 employee review for a moderator for one group, who was scolded for a “low number of posts dedicated to criticizing Hillary Clinton” and was told it was “imperative to intensify criticizing Hillary Clinton.”

Among the fans of the Russian accounts were Donald Trump Jr., who repeatedly retweeted @TEN_GOP. The account also actively pushed claims of voter fraud, which would become a mantra for Donald Trump, who warned of a stolen election before balloting, and then, after losing the popular vote, claimed that he had only lost because of 3 to 5 million fraudulent votes:

On or about August 4, 2016, Defendants and their co-conspirators began purchasing advertisements that promoted a post on the ORGANIZATION-controlled Facebook account “Stop A.I.” The post alleged that “Hillary Clinton has already committed voter fraud during the Democrat Iowa Caucus.”

On or about August 11, 2016, Defendants and their co-conspirators posted that allegations of voter fraud were being investigated in North Carolina on the ORGANIZATION-controlled Twitter account@TEN_GOP.

On or about November 2, 2016, Defendants and their co-conspirators used the same account to post allegations of “#VoterFraud by counting tens of thousands of ineligible mail in Hillary votes being reported in Broward County, Florida.”

But the efforts to interfere didn’t stop with online trolling and sock-puppeting. As previous news reports have noted, the Russians also worked to organize rallies within the U.S. They did so using a mix of falsified and stolen identities, which were then used to communicate with Trump supporters and sometimes campaign officials. In one passage, the indictment tracks the organization of a rally in Florida. It quotes this message to a genuine Facebook account:

Hi there! I’m a member of Being Patriotic online community. Listen, we’ve got an idea. Florida is still a purple state and we need to paint it red. If we lose Florida, we lose America. We can’t let it happen, right? What about organizing a YUGE pro-Trump flash mob in every Florida town? We are currently reaching out to local activists and we’ve got the folks who are okay to be in charge of organizing their events almost everywhere in FL. However, we still need your support. What do you think about that? Are you in?

In some cases, Russians paid Americans to do certain tasks, such as impersonating Hillary Clinton at a rally. “Some Defendants, posing as U.S. persons and without revealing their Russian association, communicated with unwitting individuals associated with the Trump Campaign and with other political activists to seek to coordinate political activities,” the indictment said.

The rallies produced criminal activity, according to the government. First, in order to organize rallies, the defendants were required to register with the U.S. government, which they did not. Second, they allegedly committed wire and bank fraud while attempting to move money under false pretenses. On Friday, the government also unsealed a guilty plea from Richard Pinedo, an American who acknowledged selling bank accounts to the Russians to assist them in circumventing financial laws.

The mercenary nature of the Russians’ affection for Trump manifested itself upon his victory. The goal of having elected him complete, IRA operators pivoted to create maximal discord in the new era. Operators worked to organize rallies both for and against Trump in New York on November 12, 2016. They also planned an anti-Trump rally in Charlotte, North Carolina, that month.

The level of detail in the indictment is notable. One case shows how the Russian operation remained somewhat amateurish. A defendant emailed a family member, “We had a slight crisis here at work: the FBI busted our activity (not a joke). So, I got preoccupied with covering tracks together with the colleagues …. I created all these pictures and posts, and the Americans believed that it was written by their people.” Nonetheless, given repeated Russian denials of interference, it seems unlikely that any of those indicted on Friday will face trial in the United States. (Mueller also moved to seize their assets stateside.)

The president’s reaction will be important. The indictment might further inflame his anger toward Mueller, who he has toyed with firing and reportedly even tried to fire in summer 2017, though he was talked out of it.

On the one hand, the indictment does not charge any Trump campaign officials with wrongdoing, and specifically calls any interaction with Russians in these specific activities unwitting. It also notes the ways in which the Russians organized to hurt him, as in the November 2016 New York rally. Yet so far Trump has refused to even acknowledge any Russian effort to aid him, apparently concerned that doing so undermines the legitimacy of his victory.

On Friday, he took the opportunity to reiterate that point. “Russia started their anti-US campaign in 2014, long before I announced that I would run for President,” he tweeted after the indictment’s release. “The results of the election were not impacted. The Trump campaign did nothing wrong - no collusion!” These are accurate statements about what’s included in the indictment, but the Justice Department has not made such sweeping claims about effect on the election or collusion more broadly.

The White House also issued a statement, which quoted Trump saying, “It is more important than ever before to come together as Americans. We cannot allow those seeking to sow confusion, discord, and rancor to be successful. It’s time we stop the outlandish partisan attacks, wild and false allegations, and far-fetched theories, which only serve to further the agendas of bad actors, like Russia, and do nothing to protect the principles of our institutions.” The statement said Trump was “glad to see the Special Counsel’s investigation further indicates—that there was NO COLLUSION between the Trump campaign and Russia and that the outcome of the election was not changed or affected.”

The statement sidesteps the matter of whether Trump now accepts Russian interference, which he has for so long denied. The refusal to acknowledge Russian interference was tenuous before Friday; it is now all but untenable.