Good things come to those who wait for their Uber.

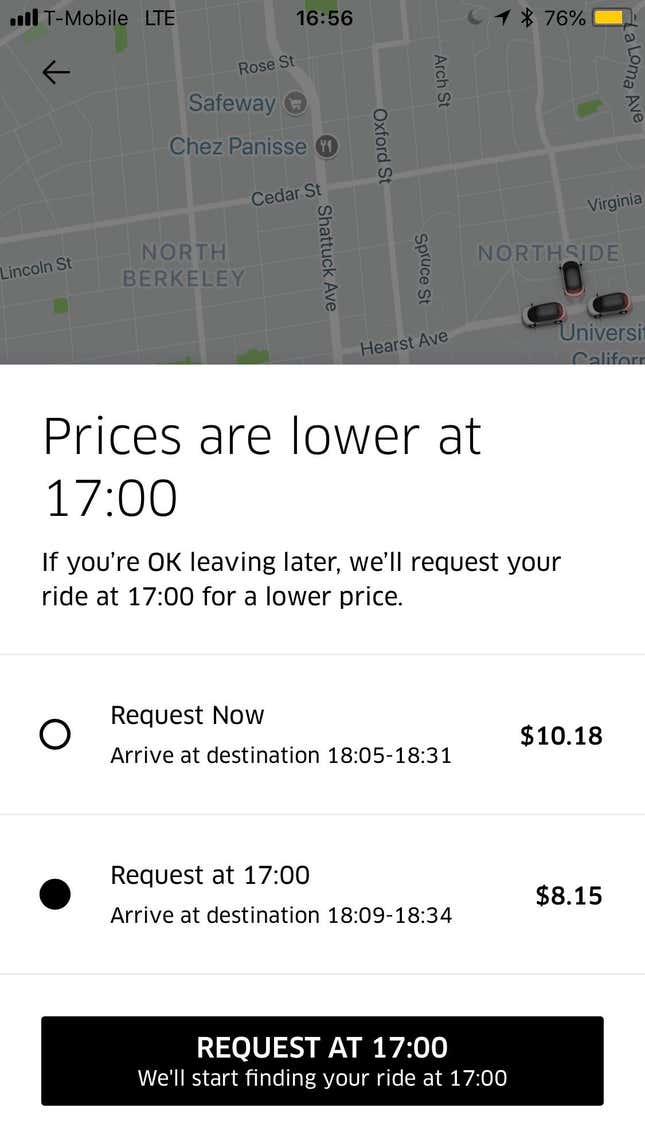

The ride-hailing company has started testing a feature that gives riders the option to trade a shorter wait for a cheaper fare. “Prices are lower at 17:00,” Uber recently advised an Uber employee who requested a ride in Berkeley, California, and tweeted a screenshot of the feature.

The image showed the Uber employee that he could request a ride “now” (4:56pm local time) for $10.18, or wait until 5pm and pay $8.15, about 25% less. “If you’re OK leaving later, we’ll request your ride at 17:00 for a lower price,” Uber’s app stated. (Update: The tweet was deleted shortly after Quartz published this story, but you can view an archived version here.)

The option to wait longer in exchange for a cheaper ride is being tested among all Uber employees in San Francisco and Los Angeles, a company spokeswoman told Quartz in an email. “Affordability is a top reason riders choose shared rides, and we’re internally experimenting with a way to save money in exchange for a later pickup,” she said.

Uber constantly varies its prices, a system known as dynamic pricing. Much like timing the market, attempting to book an Uber at the lowest price can be an ill-fated gamble. Waiting a couple minutes before booking can lead to a price that is either dramatically higher or lower.

The exact science behind Uber’s fares has also become more obscure since summer 2016, when the company quietly switched from the old model, where it flagged surge pricing to users, to one in which it quoted them the ride price “upfront” at the time of booking. This “upfront pricing” model allowed Uber to charge the rider one price, and pay the driver based on another. (A 2017 analysis by driver blog The Rideshare Guy showed the math tended to work out in Uber’s favor.)

The company has said fluctuations in dynamic prices reflect real-time changes in rider demand, driver availability, and other variable conditions, such as traffic. But the information, as an economist would say, is asymmetric. At any given moment, the driver and rider know far less about the fare—whether it’s relatively high, or low, or liable to swing up or down—than Uber does.

Uber has raised prices for riders in some of its largest US markets this year, responding to a tighter labor market, higher gas prices, and widespread frustration among drivers. “We have to make [driving for Uber] more attractive, because the alternatives are becoming more attractive,” CEO Dara Khosrowshahi said at a technology conference outside of Los Angeles in late May.

But wary of alienating passengers with higher prices, Uber is also working on several ultra-cheap ride options. These include Express Pool, a version of Uber’s shared UberPool that asks the rider to walk to a nearby street corner with the goal of picking up multiple people at once. Uber has poured tons of money into Pool discounts in an effort to get more people to share their rides. Khosrowshahi said at the conference that Uber was spending “hundreds of millions of dollars” on Pool. “A very, very important push for us is to innovate to lower cost,” he said.

Offering riders longer wait times in exchange for cheaper fares is another way Uber could keep prices low for the most price-sensitive customers. It’s also a strategy that makes a lot of sense. Uber tends to charge more when lots of people in the same area request a ride at the same time (“demand is off the charts!” as the old surge pricing warning went). One function of those higher prices is to attract more drivers to the area, thereby evening out supply and demand.

You can look at the option Uber is testing among employees now as the inverse approach: Instead of charging customers more to get a ride now, when demand is high, Uber tells them they can pay less if they’re willing to wait, shifting some of that demand to the future.

Uber declined to provide additional details on the test, for example, how long a rider might be asked to wait and in exchange for what discount. For a company that operates on Uber’s scale—4 billion rides across 600 cities in 2017 alone—being able to move little bits of demand, even by just a few minutes, could be a powerful tool for keeping fares low and wait times short.

Uber co-founder and former CEO Travis Kalanick used to talk about how the point of surge pricing was to keep Uber reliable. “Higher prices are required in order to get cars on the road and keep them on the road during the busiest times,” he wrote on Facebook in December 2013, after the company had angered users in New York with sky-high surge during a bad snowstorm. “This maximizes the number of trips and minimizes the number of people stranded.”

The implicit assumption was that Uber customers wanted a ride as fast as they could get one, whatever it might cost. The system being tested now, on the other hand, acknowledges a different kind of rider—someone for whom saving a little time is less valuable than saving a little money.