Jackie Chan has given the same American talk show interview for nearly 30 years. He describes the grueling training he endured from ages 7 to 17 at the China Drama Academy. He talks about how he gets recognized in even the most isolated places around the world. He lets David Letterman or Conan O’Brien feel the hole on his head from when he cracked his skull. He sweep-kicks bottles or somersaults over their desks. And in many of these interviews, Chan has expressed the same sentiment, usually after the host introduces him with a karate chop flourish: “I’m an actor, I want to do some drama.”

Since at least 2004, Chan has talked about “becoming a true actor” like Robert De Niro, Robert Redford, Clint Eastwood, or his Kung Fu Panda co-star Dustin Hoffman. And last year, when Chan received an honorary Oscar, he talked about how, despite all his global acclaim, his father continued to ask him when he would win an Academy Award. With the release of The Foreigner, a traditional action thriller that pits him against Pierce Brosnan, and Chan's first wide-release film in seven years, he may finally have his chance to be taken seriously. But history tells us that for the average American moviegoer, viewing Chan as a serious actor is a tough sell, despite the decades of experience he has had as a Hong Kong director, actor, and stunt coordinator.

Lo Wei, the Hong Kong director who made The Big Boss and Fist of Fury, the films that turned Bruce Lee into a veritable action star in China, began looking for the next Bruce Lee after Lee died unexpectedly in 1975. He thought Chan might fit the bill and had him sign a contract with Lo Wei Productions. Chan played the lead, as Lee’s brother, in the 1976 Fist of Fury sequel New Fist of Fury. But after that, plus six more failed attempts to make Chan a star, Chan conspired with director Chen Chi-hwa to make Half a Loaf of Kung Fu, which spoofed other kung fu films by poking fun at the machismo usually on display in such movies. Aside from when he eats spinach Popeye-style and becomes a fighting machine, Chan — the film’s star, stunt coordinator, and, essentially, creative director — is helpless against his opponents. Lo called Half a Loaf “rubbish” and shelved it for two years. But once the film hit theaters in 1980, it became a hit in Southeast Asia.

“Bruce was a success because he did things that no one else was doing,” Chan once said to a Hong Kong studio exec, according to his autobiography I Am Jackie Chan. “Now everyone is doing Bruce. If we want to be successful too, we need to be Bruce’s opposite.”

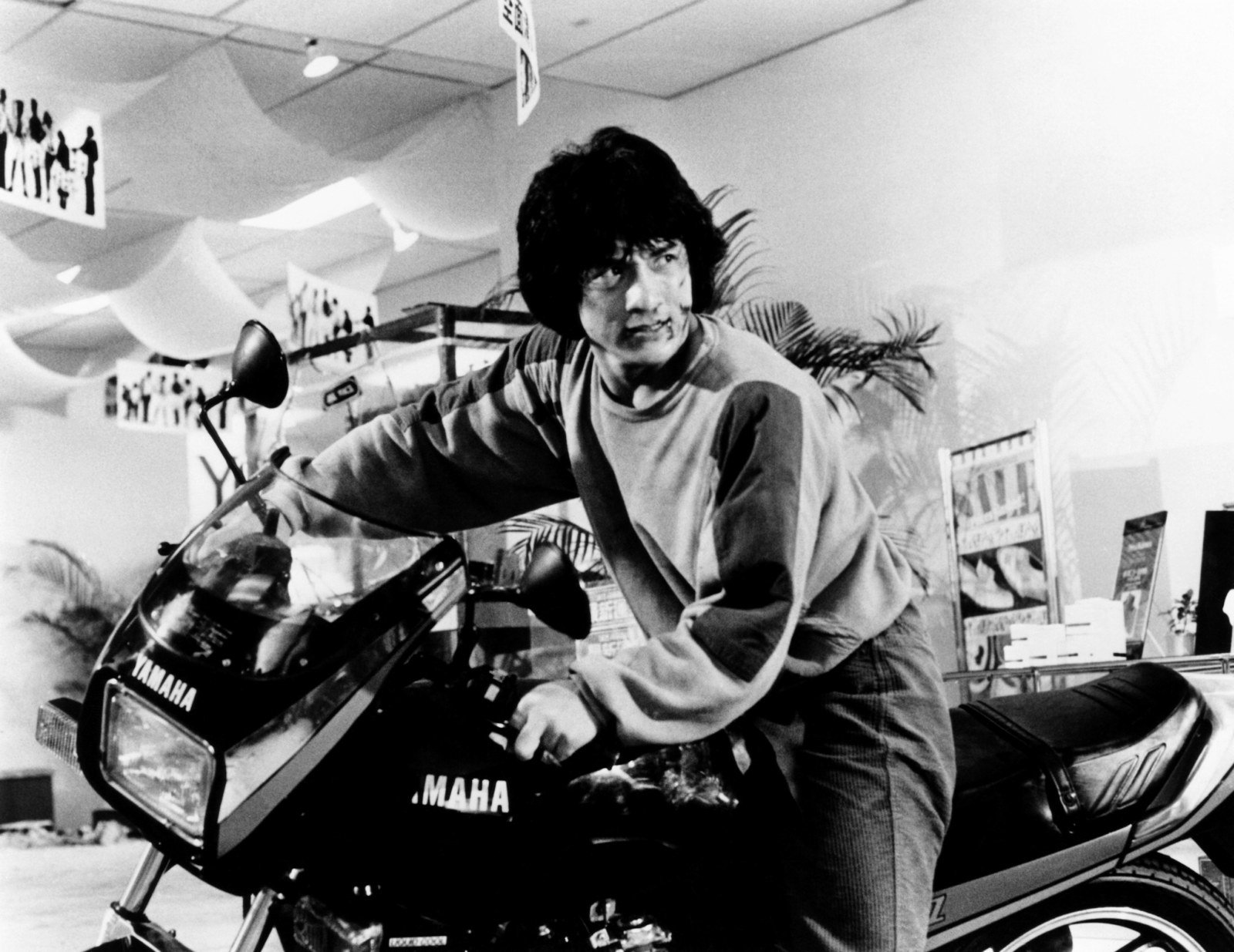

For the next two decades leading up to Rush Hour, Chan established his singular filmmaking style with Hong Kong action comedies like Drunken Master, Wheels on Meals, Police Story, Armour of God, Twin Dragons, City Hunter, Mr. Nice Guy, Who Am I?, and the dozen-plus sequels they spawned. He directed his first film in 1979 (Fearless Hyena), received his first acting award nomination in 1984 (for Project A), and broke Hong Kong box office records (with My Lucky Stars, which grossed $30 million).

Chan became famous for how he could really fight, but also really, really get hurt. During his action sequences, which could be up to 20 minutes long, his face would scrunch up in agony, his body would bruise, and his four-times-broken nose would bleed. He'd resort to using clothing, ladders, and dinner plates as self-defense, anything and everything but a gun. There isn't a single Jackie Chan fight scene that hasn't looked or felt painful. By the time the blooper reel rolls at the end of each movie, the audience understands that Chan came out on top not just because of his mastery, but because of human virtues like perseverance and resourcefulness. Chan would have to throw a hundred punches in lightning-quick, expertly choreographed succession to survive whoever would gang up on him. And without resorting to Hollywood shortcuts like cutaways or closeup shots like in most action films, Chan made sure the audience could actually count each punch.

Chan first attempted to break into Hollywood with 1980's The Big Brawl, directed by Enter the Dragon’s Robert Clouse. Like Lo, Clouse wanted Chan to fight like Bruce Lee — slowly, deliberately, and forcefully. The film bombed. In 1981 he appeared in The Cannonball Run with Burt Reynolds, Roger Moore, Dean Martin, and Sammy Davis Jr. The Cannonball Run did become the seventh-biggest film in the US that year, though Roger Ebert panned it: “They didn’t even care enough to make a good lousy movie.” Meanwhile, between the lack of creative control over the action scenes, and the interviews with clueless reporters who couldn’t even distinguish karate from kung fu, Chan felt humiliated. “Hollywood rejected me and turned me into something silly and shameful,” he writes in his autobiography. Chan wouldn’t return to Hollywood until five years later, to work with the now-obscure James Glickenhaus for 1985’s The Protector. He was so unsatisfied with how Glickenhaus directed the action scenes, he filmed extra footage to restructure the final scene for The Protector's Chinese print.

“Jim told me he didn’t want Jackie to do any of his long fights,” said American Ninja star Steve James, in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon producer Bey Logan’s book Hong Kong Action Cinema, “but I said, ‘Jim, that’s what makes Jackie popular! We all knew that when the first Police Story came out that that’s what The Protector should have been.”

Police Story, directed by Chan, was such a Hong Kong blockbuster that it spawned a hit franchise with four more installations. Scenes from the 1985 original have been copied in Sylvester Stallone and Kurt Russell's Tango and Cash, Brandon Lee's Rapid Fire, and Bad Boys II. Yet in 1996, when Chan tried to re-release Police Story 3: Supercop in the United States, he lost creative control to twenty-something editors who chose a dance remix of “Kung Fu Fighting” for the end credits. “The American production [studio], they trust them [when] they only spend 10 days, one week, looking at the movie,” Chan said during the DVD extras interview. Keep in mind that Chan had just starred in Rumble in the Bronx, his first movie to become a box office success at home and in the United States.

Director Brett Ratner thought his upcoming 1998 buddy comedy Rush Hour was a perfect compromise between Eastern and Western sensibilities and thus the perfect vehicle for Chan. He was such a fan of Chan’s films, he would reference them on set while allowing Chan to improvise the Rush Hour fight scenes: “Remember in Police Story 2, Jackie, when…” But Ratner also wanted to keep fight scenes at two minutes or less, because “American audiences have a very different attention span.”

Rush Hour grossed $100 million in the US, making Chan a cultural phenomenon there, finally. But the attention was often humiliating. Demonstrating kung fu on TV made Chan feel like a “trained dog,” as his autobiography says, though he kept doing it anyway — that is what his former manager called “the price to pay for success” in America. Meanwhile, Hollywood attributed more of the film’s success to co-star Chris Tucker, according to I Am Jackie Chan’s co-writer Jeff Yang.

Chan later said on his official site that the Rush Hour franchise was his least favorite of the film series he starred in because he felt like he compromised too much. While making the first Rush Hour, he would argue with cinematographer Adam Greenberg until Greenberg walked off set in frustration. “I’ve seen the results when Hollywood people try to make ‘Jackie Chan’-style movies,” Chan says in his autobiography. “It looks ridiculous. There’s no continuity to the action, no flow; everybody’s flying around, and there are too many quick cuts, and it’s more like a trip to the amusement park than a kung-fu fight.” (He’s right — just watch filmmaker Tony Zhou’s breakdown of how Chan’s fight scenes compare to Hollywood’s.)

In America, Chan wouldn't get his first action director credit until Shanghai Knights, the 2003 sequel to Shanghai Noon. The basic premise of both films, Imperial China meets the Wild Wild West, was also his idea. Yet even after that, and again with 2010’s The Karate Kid remake (Chan’s last film to get a wide release), he kept getting offered stereotypical roles — “either Hong Kong Cop or Killer from China,” as he complained back in 1998. (September’s The Lego Ninjago Movie isn’t much better. Chan voices a “Master Wu” mentoring a young blond hero played by Dave Franco. Rush Hour’s Ratner is an executive producer, and it shows: Only a self-proclaimed martial arts fan like him would have Master Wu spar with a wooden training dummy, as Chan did in Rumble. But once again, Chan’s voice is outnumbered and overwhelmed by white ones.)

Consequently, The Foreigner, directed by GoldenEye and Casino Royale's Martin Campbell, is a welcome departure from such roles. Chan was already on board by the time Campbell signed on. But Campbell has since become the rare director who has seen Chan’s talent, and that revelation comes from an unexpected source: The Karate Kid. “There's a marvelous scene where [Mr. Han] destroys this car,” Campbell said to GQ in September for a profile of Chan. “I think it was a car crash that killed his family, and he survived, and every year he reconstructs and remodels this car to perfect condition, and on the day of their death he smashes it with a sledgehammer, as a kind of wailing wall, as it were. He’s excellent in that film. That really was the clue for me that he could do this.”

Campbell’s instincts were right. The Foreigner’s cat-and-mouse game pits Chan, playing a Vietnamese-born Londoner avenging his daughter’s death, against a former IRA leader turned British government official with convoluted allegiances (Pierce Brosnan). Chan is still easy to root for. He appears a decade older than his character’s supposed age of 61, with his pronounced gray hairs and wrinkles, hobbling. But he also has a quiet intensity that outshines his co-star Brosnan’s bluster. Once Chan completes his personal mission, the stream of tears he sheds feel authentic and earned.

Chan also had more behind-the-scenes involvement in The Foreigner, says Campbell, bringing in one of his own stunt directors to guide the action scenes. Whether he will ever be critically and commercially recognized stateside for his own Rocky remains to be seen. (At least Stallone, now a good friend, will cheer him on.) For now, he is being as resilient and resourceful as he has ever been doing death-defying stunts on screen. While he has pretty much confirmed that Rush Hour 4 begins production next year, he told the Associated Press in 2005 that he only does American films like those to fund projects where he has autonomy back home. He has also updated his plea to American producers for more diverse roles. “Can I have something different like La La Land?” he told Stephen Colbert and Chelsea Handler while promoting The Foreigner this week. Chan may still be repeating himself, but at least the conversation surrounding him might finally, actually change.

Christina Lee is a culture journalist who has written for Rolling Stone, The Guardian and Red Bull Music Academy. In 2014 she won an Atlanta Press Club award for her co-write on the Creative Loafing cover story “Straight Outta Stankonia.”