Over thirty thousand runners began the Boston Marathon this morning in Hopkinton, MA, some having trained and run for years to get to this point. Their completion medals will be well-earned. From your heart, through your circulatory system, to your leg muscles and kidneys, running a marathon is sort of like putting your entire body through a meat grinder.

Some run with charities and keep a slower pace. Others, in elite classes of runners, will finish the 26.2 miles in just over two hours. One thing all of today’s marathon runners will share is an incredible amount of wear and tear on their bodies.

Body temperature rises feverishly

Racers start out in Hopkinton with a normal body temperature of around 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit. But by the end of the race, according to Mark Perazella, MD, a Professor of Medicine at Yale University School of Medicine, their core temperatures will be much higher, at around 102 degrees, with the rare runner occasionally reaching 103 by the finish line—similar to a high-grade fever.

The higher the core body temperature, the harder the heart needs to pump blood to maintain a steady flow to the runner’s muscles. “Blood flow increases significantly to [a runner’s] skin to cool it down, stealing it from skeletal muscles,” Dr. Gregory Lewis, Director of the Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing Laboratory at Massachusetts General Hospital explained.

By the end of the race, after the sweat on the runners’ bodies begins to cool, their core temperatures start to plummet, putting them at risk for hypothermia. That’s why many marathon runners use Mylar blankets to warm themselves.

The kidneys take a hit

A team of Yale researchers led by Dr. Chirag Parikh studied 22 runners in the 2015 Hartford Marathon, collecting blood and urine samples before the race, immediately after the race, and 24 hours later. In a study published in the American Journal of Kidney Diseases, the researchers wrote that 82 percent of runners showed Stage 1 Acute Kidney Injury immediately after the marathon—a condition where kidneys have stopped filtering toxins from blood. That sounds really bad! But in the long run, it might not be.

According to Perazella, who co-authored the study, kidney damage might be the result of decreased blood flow to kidneys during the marathon, compounded by dehydration and the rise in core body temperature.

“We saw that three-quarters had [kidney] injury from a urine microscopy test,” Perazella told Gizmodo. Other studies on renal failure have reached similar conclusions, including one by the Asian Pacific Society of Nephrology which looked at biomarkers and serum creatinine levels—indicators for kidney function—and recognized acute kidney injury after marathon running.

It’s currently unknown if renal problems, which persist for several days, cause any long-term kidney damage. Most runners tend to recover from acute kidney injury within two weeks, according to Perazella. But: “No one has formally studied kidney function longer than two weeks after marathon running in those with kidney injury,” he said.

Energy production goes into overdrive

The human body burns several things in order to keep moving. Carbohydrates, which are stored as glycogen (or glucose) in the muscles and in the liver, are our primary energy source. Our bodies also burn fat, but at a much lower level. According to David Mark Ph.D, a nutritional performance consultant, runners begin the marathon with a calorie burning rate of 150 calories an hour. He said, “the moment they start running, they’re up to 700-800 calories an hour.”

The average body stores 500 grams of glycogen, or 2000 calories of glucose. On average, every mile run burns off 100 calories of glucose, according to Mark. That means in 20 miles, you’ve burned your entire supply. This is when runners hit the infamous “wall,” also known as the point where they feel like they can’t go any further.

At that point of glucose depletion, a runner’s body is relying on mostly fat and protein for fuel. The heart, hamstrings, and quadricep muscles need more help with every mile, and have a harder time acquiring oxygen.

But there’s a way around the wall. John Hadcock, Ph.D. works as a senior director of a pharmacology company, and is a six-time Boston Marathon runner currently running his seventh. He told Gizmodo that the most efficient participants train to “run slowly for the first part of the marathon,” and maintain a steady pace. That way, their bodies burn extra fat, and only use about 80 calories of glucose per mile, saving “a little more” for the end of the marathon.

Many runners spend Friday or Saturday night loading up on carbohydrates at pasta dinners. Hadcock said, “Three days before the marathon, we switch to eating carbs, very little fat, and a little protein. That tops off the fuel for your muscles in the form of glycogen (for carbs).”

There’s another reason runners want to avoid running out of glucose aside from the wall. Glycogen is stored in the muscles and liver, with 500 grams being the full capacity that can be stored. Hypoglycemia, or low blood sugar, is held at bay by runners when they stop to grab sugary gels and sports drinks like Gatorade along the course. On rare occasions, hypoglycemia can lead to a runner passing out. On the other hand, too many gels can increase glucose levels too much, leading to headaches and nausea.

Change in your heart and blood flow

Many runners train to run according to heart rate. Adults typically have a heart rate from 60-100 beats per minute, while trained athletes and endurance runners have somewhat lower heart rates, around 40-60 beats per minute. If a runner trains at 140 beats per minute, he or she typically wants to remain at that rate throughout most of the marathon, until the final sprint.

Dr. Gregory Lewis told Gizmodo that studies have found that the right chamber of the heart dilates disproportionately to the left chamber during the race, with the left ventricle “bearing the burden” of the marathon. Researchers have also observed that runners create a byproduct of troponin inside heart cells, which is used by doctors to see if someone has cardiac damage if suffering a cardiac episode.

In rare circumstances, troponin can indicate that the runner is at risk of a heart attack. According to a 2012 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy was the leading cause of death in a pool of 59 runners who suffered cardiac arrest. The information was obtained from a database of cardiac deaths during marathons from January 1, 2000, through May 31, 2010.

While the condition of your heart is an important consideration if you’re thinking of running a marathon, there’s a misconception that runners must have big lungs. “Lungs aren’t particularly dynamic, and not as much of an issue as the cardiovascular system,” Lewis said. He explained that blood redistributes during a marathon, with more blood going primarily to the brain, heart, and muscles over the the stomach and abdominal organs.

Muscle and joint damage, exhaustion and hitting “the wall”

Many spectators will see runners hunched over throughout the marathon, but even more so near the end. According to Hadcock, that’s because of an increase in the amount of lactate in their muscles, which results in cramps. Lactate builds up when a runner burns glucose at a faster rate than he takes in oxygen, for instance, during the final sprint.

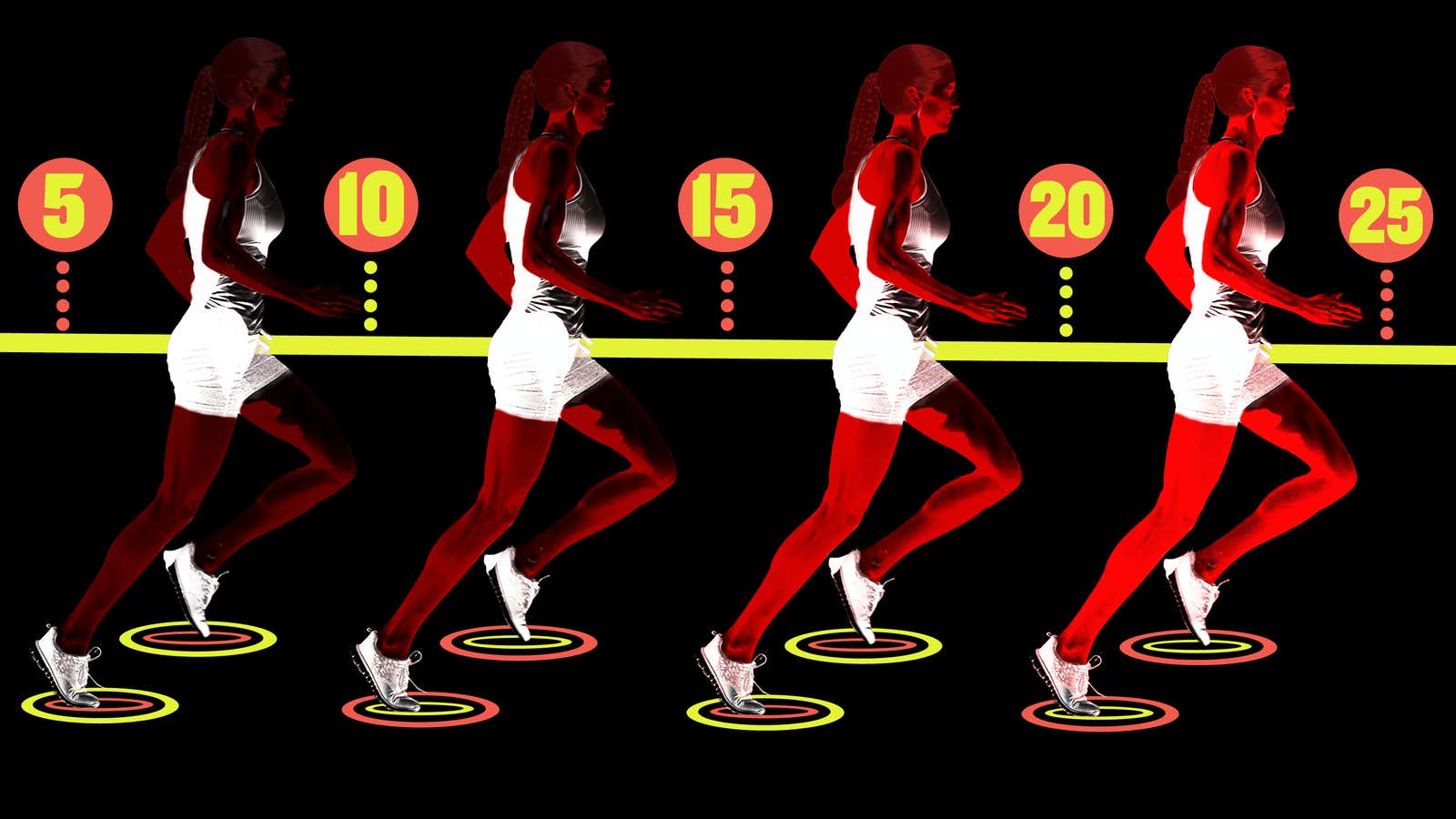

Toward the end of a marathon is also when the effects of tissue damage on the muscles and joints really starts to be felt, too. According to Mark, this damage is unavoidable. “Especially more on the hills going downhill,” he told Gizmodo. “Your foot is cushioning with each step.”

“When it comes 15 to 20 miles in, you’re going to jolt harder,” he added.

At the infamous Heartbreak Hill, the last of four hills near Boston, this gets really bad. By Heartbreak Hill (mile 20.5), runners are exhausted, and hit the notorious wall. At that point, Mark said, “you’ve almost exhausted your carb stores, and your blood sugar is dropping. You’re running on an almost empty tank. The brain only operates on glucose, so people start to lose focus, get fuzzy vision, and slow down.”

Frank Biello Jr, 36, is running his second Boston Marathon today. He described the final stretch to Gizmodo. “It’s mostly nerve and muscle pain, from the wear and tear. Once you hit the wall, it’s mind over matter. You have to do whatever you can to keep your mind focused on everything else, and the positive.”

This is made easier by the crowds, which become bigger toward the end of the marathon. More than 500,000 crowd spectators fill the streets to cheer on their loved ones, and celebrate the endurance of the human body and spirit.

Sarah Betancourt is a New England-based reporter, and a former fellow at the Stabile Center for Investigative Journalism at Columbia University. Follow her @sweetadelinevt.